by Philip Davenport and Julia Grime

NYC, October 2011

Erica Baum: I guess I feel like what I’m doing is a kind of writing but it’s a writing through what I find, and somehow it feels like it’s my writing even though everything I do is what I’m finding, so that’s kind of the common thread through all the projects.

Philip Davenport: And what is it that you look for, and what do you find?

EB: Well there’s a humour and a rhythm: those are the two things that anchor me and steer me. So, I’ll feel a flow of words, but I also like to work within constraints, so it’s not simply what I find but something that I find within a system. And the first project I did with the card catalogues, or one of the first projects I did, the idea was there there’s a system and the system is giving you a sense of an institution that generated this system but also generates incidental texts that we then encounter and can relate to in different ways. So that’s been the spark that gets me going: there’s some organising principle that generated this and then I can come in and find things and take it somewhere else.

PD: What started that?

EB: It’s hard to say exactly. With Dog Ear I feel like I can say in a way it’s an homage to just loving to read, and so maybe that’s what all this is really all about: just that I love to read. I did a project before I did the card catalogues where I was looking at blackboards when I was in graduate school at Yale, and I would go to the classrooms and I would look at what was left on the board in between classes, so there were traces of words and partially erased, and you had this feeling of this sort of ephemeral moment and traces of this moment but then you weren’t in the class and it’s this in-between moment. And so, there’s a playfulness in relating to something where, again, you know there is information, there was something someone was really trying to inform, and yet our relationship to it is a little bit at an angle, it’s sort of oblique. I think maybe loving to read is the basic, basic behind it all.

PD: There’s an attention to ideas of narrative in what you do, but there’s also a great focus on the material.

EB: Yeah, and I think that’s photographic. Having studied photography and traditional photography, there is just within straight photography a whole idea of a the found word within a landscape; like Walker Evans, Atget, [Editor’s note: Eugène Atget 1857-1927 was a French photographer noted for documenting the architecture and street scenes of Paris] or any of those, Brassai… [George Brassaï 1899-1984 Hungarian photographer, sculptor, and filmmaker rose to international fame in France in the 20th century. He was one of the numerous Hungarian artists who flourished in Paris beginning between the World Wars. In the early 21st century, the discovery of more than 200 letters and hundreds of drawings and other items from the period 1940–1984 has provided scholars with material for understanding his later life and career.] So there’s a feeling that within a field you’ll see words. And so I’m just taking that into other places, in a ways it’s really the same thing. It’s just deciding what the field is, and then looking.

PD: Looking at your work, there’s a tremendous fascination with time and sequence.

EB: I think that’s the rhythm, for me, that is what I mean by rhythm: it’s the feeling of something, and then something, and then something.

PD: Yeah, but it also, there seems to me, an attention to the past. The piano rolls for instance, that’s a really antiquated piece of technology.

EB: And again, I think that comes from photography, because I’m looking for things that actually exist, and have texture, and have a place. So I’m open to computers, but at the same time in terms of trying to find a thing to photograph, it has to have some existence, some texture. These older, like with the piano rolls, the fact that they sort of give you a sense of the industrial age and things being mechanically reproduced on mass, and yet at the same time they have this quirky character to them that we’ve lost in most of the things we find now because they’re so seamlessly produced or don’t exist physically at all. And with the card catalogues, when I initially started that it was meant to be quotidian thing, even blackboards too and now they don’t really use blackboards they use dry erase boards or smart boards, but these were meant to be quotidian things that are out there that we’re looking at, and then as I was doing it, with the card catalogues in particular, I started seeing card catalogues being decommissioned and being put away, and then it became a documentary project in a different way, in addition to being this quotidian thing. So that’s been a thread because I’m always looking for tangible things.

PD: …It’s also about not being seamless. There seems to be something about the relationship to age and to the texture of age?

EB: Well, it’s also the feeling that there’s something individual within the factory. Like the idea that something’s produced this way and yet you can feel the sense, like with the card catalogue the actual idiosyncrasies of the particular librarian, so again you have a system which is meant to be applied everywhere and yet you have an individual within the system and that kind of draws that out... I feel like with a lot of these projects I’m drawing attention to something that otherwise might be forgotten or neglected, it makes you notice it and appreciate it more. It’s been very poignant for me with every single project that I’m not necessarily intentionally starting out that way but even with something like Dog Ear to realise that, even in New York anyway, there aren’t that many second hand bookstores anymore. You know, I picture rows and rows of old paperbacks and then… where are they? And it’s something that you realise that this is something that people need to appreciate, because we can’t take it for granted.

PD: I was talking to Steve Zultanski, who is a poet, and he was saying that these little bookshops are just disappearing.

EB: Paris still has quite a lot of them it’s really nice that way. […]

Julia Grime: Manchester’s only got about two now, I think.

PD: (Aside) Personally, I blame the influence of Noel Gallagher.

JG: We’ve got Hay-on-Wye, which is a little village that has nothing but bookshops.

PD: Julia took me there; it was last year wasn’t it?

JG: We were going to a philosophy festival though, so the bookshops kind of ended up… we were only there for a day and we went to a lot of lectures so…

PD: We hardly saw the bookshops.

JG: You ended up in the poetry bookshop looking at stuff you’d already read!

PD: I was trying to resist and then I wound up in the poetry bookshop – ironically, because Julia introduced me to some philosophy things, so the conference was her initiative and it was a conference about information, the handling of information, it was all about virtual stuff. So we were sitting in Hay-on-Wye talking about technology and not about books.

JG: The whole idea that you can’t have total knowledge anymore because there’s so much stuff and so much information, so it becomes much more about how you stream that information. And that, moving forward, it’s how you use the internet or whatever source it’s going to be, rather than the actual information itself. So a hundred years ago we knew that “Man” knew everything, and you can’t do that anymore, so you have to edit everything, or know how to.

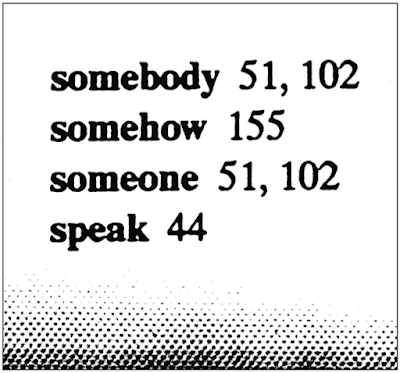

EB: That’s part of what initially started me with the index project was I was looking at some very old books and the index as the range of information was, to me, that thing where you felt like you could have this range because the range was reasonable for one person or the person that makes the book. And it’s different now, it’s much more specialised and narrow, and you don’t see that broad crazy range that you would have seen, for that reason: there’s just too much and it’s just more specialised.

PD: I see what you mean, in a way those juxtapositions that you’re making there, you can’t make sense of them - they’re really wide aren’t they?

EB: Right, it’s not really the way we think now because we tend to think within our specialities.

PD: … Often the two strands of poets and artists can be doing similar things and yet they’re not aware of each other. You actually have heard of Charles Bernstein and you know Kenny Goldsmith as well… (the Introduction) … in Dog Ear is by Kenny. How does it differ, being written about by a poet? … Does that feel appropriate?

EB: Yeah it does… it’s as important to me to be understood in the poetry world as it is to be understood in the art world. And it’s kind of a big stretch to hope to get either of those things, and get any recognition or attention from either, but I want both. It’s exciting for me, I was really happy about the way the Kenny wrote about that because he really took it on and took the words on as much as the way the words looked. It’s really important to me, and I’ve been excited by his work for a long time.

PD: Julia was just saying that he mentions Pound in there. How do you relate to that strand?

EB: Well, I think it’s very exciting, I don’t know what to say, I’m a sort of an auto-didact when it comes to poetry. When I was in college I studied Chinese and Japanese poetry in translation, and I studied Japanese actually, so I have a sense of language as a picture from studying Japanese and actually even the whole idea of verticality and looking at different ways… So, I don’t know, it’s hard to put all the strands together and make a real narrative out of it, but that’s there. As I said, auto-didactic - read biographies of Pound and I always loved Gertrude Stein even when I was a teenager, but I mean… I don’t know!

PD: That’s a very fair answer.

Interview from THE DARK WOULD language art anthology (pub. 2013)

Volume 2

ABOVE:

Erica Baum, Untitled (Somebody Somehow), 1999 (Index)

Untitled (Rain), 1999 (Index)

BELOW:

Erica Baum,Untitled (Ooze Deep Sea), 2000 (Index)

Comments

Post a Comment